On Dec. 9, 2016, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) arrested Sean Sharma, a 26-year-old student at the University of California accused of using a booter service to knock a San Francisco chat service company’s Web site offline.

Sharma was one of almost three dozen others across 13 countries who were arrested on suspicion of paying for cyberattacks. As part of a coordinated law enforcement effort dubbed “Operation Tarpit,” investigators here and abroad also executed more than 100 so-called “knock-and-talk” interviews with booter buyers who were quizzed about their involvement but not formally charged with crimes.

Stresser and booter services leverage commercial hosting services and security weaknesses in Internet-connected devices to hurl huge volleys of junk traffic at targeted Web sites. These attacks, known as “distributed denial-of-service” (DDoS) assaults, are digital sieges aimed at causing a site to crash or at least to remain unreachable by legitimate Web visitors.

“DDoS tools are among the many specialized cyber crime services available for hire that may be used by professional criminals and novices alike,” said Steve Kelly, FBI unit chief of the International Cyber Crime Coordination Cell, a task force created earlier this year by the FBI whose stated mission is to ‘defeat the most significant cyber criminals and enablers of the cyber underground.’ “While the FBI is working with our international partners to apprehend and prosecute sophisticated cyber criminals, we also want to deter the young from starting down this path.”

According to Europol, the European Union’s law enforcement agency, the operation involved arrests and interviews of suspected DDoS-for-hire customers in Australia, Belgium, France, Hungary, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the U.S. Europol said investigators are only warning one-time users, but aggressively pursuing repeat offenders who frequented the booter services.

“This successful operation marks the kick-off of a prevention campaign in all participating countries in order to raise awareness of the risk of young adults getting involved in cybercrime,” reads a statement released Monday by Europol. “Many do it for fun without realizing the consequences of their actions – but the penalties can be severe and have a negative impact on their future prospects.”

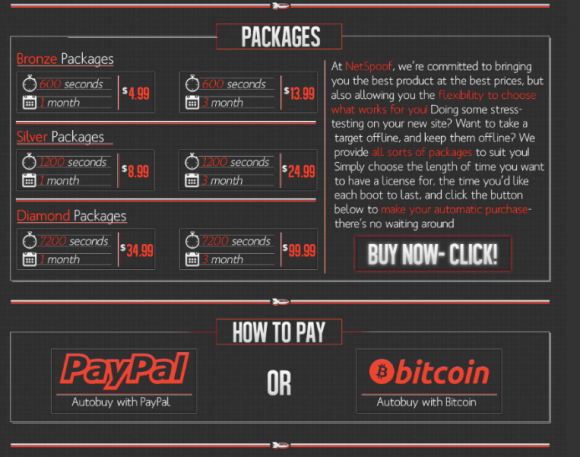

The arrests stemmed at least in part from successes that investigators had infiltrating a booter service operating under the name “Netspoof.” According to the U.K.’s National Crime Agency, Netspoof offered subscription packages ranging from £4 (~USD $5) to £380 (~USD $482) – with some customers paying more than £8,000 (> USD $10,000) to launch hundreds of attacks. The NCA said twelve people were arrested in connection with the Netspoof investigation, and that victims included gaming providers, government departments, internet hosting companies, schools and colleges.

The Netspoof portion of last week’s operation was fueled by the arrest of Netspoof’s founder — 20-year-old U.K. resident Grant Manser. As Bleeping Computer reports, Manser’s business had 12,800 registered users, of which 400 bought his tools, launching 603,499 DDoS attacks on 224,548 targets.

Manser was sentenced in April 2016 to two years youth detention suspended for 18 months, as well as 100 hours of community service. According to BC’s Catalin Cimpanu, the judge in Manser’s case went easy on him because he built safeguards in his tools that prevented customers from attacking police, hospitals and government institutions.

ANALYSIS

As a journalist who has long sought to expose the booter and stresser industry and those behind it, this action has been a long time coming. The past three to four years have witnessed a dramatic increase in the number and sophistication of booter services.

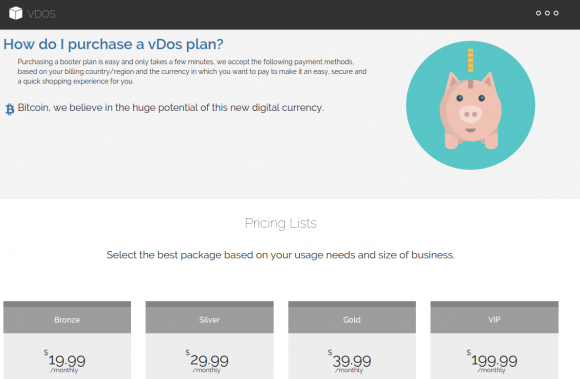

In September 2016, this site was the recipient of a record-sized DDoS attack that knocked this site offline for several days. The attack came hours after a story I wrote about the now-defunct booter service vDOS was punctuated by the arrest of two 18-year-old Israeli men allegedly tied to the business. I was able to track them down because vDOS had been massively hacked, and huge troves of data from the service’s servers were shared with KrebsOnSecurity.

vDOS had been in business for four years, but records about how much the business made were incomplete; only two years’ worth of DDoS customer data was available (the rest had apparently been wiped from the server). But in that two years, the records showed that more than 150,000 customer paid in excess of $600,000 to launch DDoS attacks on targeted sites.

The demise of vDOS exposed a worrying trend in DDoS-for-hire attack services: The rise of hyper-powered booter services capable of launching attacks that can disrupt operations at even the largest of Web sites and hosting providers.

Hours after the Septemeber attack swept KrebsOnSecurity offline, the same attackers hit French hosting giant OVH with an even larger DDoS-for-hire attack. On Oct. 21, 2016, Internet infrastructure provider Dyn was hit by a very similar attack. All three attacks involved collections of hacked computers powered by DDoS-based malware called “Mirai.” This malware doesn’t infect Windows computers, but instead worms its way into Linux-based systems that run on many consumer hardware products like wireless routers, security cameras and digital video recorders that are left operating in factory-default (insecure) settings.

Security experts say the crime machine that caused problems for Dyn was not the same one that was used to knock my site offline in September. That’s because at the beginning of October the miscreant responsible for creating Mirai leaked the source code for the malware online. Since then, dozens of new Mirai robot networks or “botnets” have been spotted being used to launch cyberattacks — including the one used to attack Dyn. And in some cases, the criminals at the helm of these weapons of mass disruption are renting out “slices” or shares of the botnet to other crooks, typically at the rate of several thousand dollars per week.

I applaud last week’s actions here in the United States and abroad, as I believe many booter service customers patronize them out of some rationalization that doing so isn’t a serious crime. The typical booter service customer is a teenage male who is into online gaming and is seeking a way to knock a rival team or server offline — sometimes to settle a score or even to win a game. One of the co-proprietors of vDos, for example, was famous for DDoSsing the game server offline if his own team was about to lose — thereby preserving the team’s freakishly high ‘win’ ratios.

But this is a stereotype that glosses over a serious, costly and metastasizing problem that needs urgent attention. More critically, early law enforcement intervention for youths involved in launching or patronizing these services may be key to turning otherwise bright kids away from the dark side and toward more constructive uses of their time and talents before they wind up in jail. I’m afraid that absent some sort of “road to Damascus” moment or law enforcement intervention, a great many individuals who initially only pay for such attacks end up getting sucked into an alluring criminal vortex of digital extortion, easy money and online hooliganism.

Source: krebsonsecurity.com